Alligator

An alligator is a crocodilian in the genus Alligator of the family *Alligatoridae*. The two living species are the American alligator (*A. mississippiensis*) and the Chinese alligator (*A. sinensis*). In addition, several extinct species of alligator are known from fossil remains. Alligators first appeared during the Paleocene epoch about 66 million years ago.

The name "alligator" is probably an anglicized form of el lagarto, the Spanish term for "the lizard", which early Spanish explorers and settlers in Florida called the alligator. Later English spellings of the name included allagarta and alagarto.

An average adult American alligator's weight and length is 790 lb and 13.1 ft, but they sometimes grow to 14 ft long and weigh over 450 kg 990 lb. The largest ever recorded, found in Louisiana, measured 19.2 ft. The Chinese alligator is smaller, rarely exceeding 6.9 ft in length. In addition, it weighs considerably less, with males rarely over 99 lb.

Adult alligators are black or dark olive-brown with white undersides, while juveniles have strongly contrasting white or yellow marks which fade with age.

No average lifespan for an alligator has been measured. In 1937, an adult specimen was brought to the Belgrade Zoo in Serbia from Germany. It is now at least 80 years old. Although no valid records exist about its date of birth, this alligator, officially named Muja, is considered the oldest alligator living in captivity.

American alligators are found in the southeast United States: all of Florida and Louisiana; the southern parts of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi; coastal South and North Carolina; East Texas, the southeast corner of Oklahoma, and the southern tip of Arkansas. According to the 2005 Scholastic Book of World Records, Louisiana has the largest alligator population. The majority of American alligators inhabit Florida and Louisiana, with over a million alligators in each state. Southern Florida is the only place where both alligators and crocodiles live side by side.

American alligators live in freshwater environments, such as ponds, marshes, wetlands, rivers, lakes, and swamps, as well as in brackish environments. When they construct alligator holes in the wetlands, they increase plant diversity and provide habitat for other animals during droughts. They are, therefore, considered an important species for maintaining ecological diversity in wetlands. Farther west, in Louisiana, heavy grazing by coypu and muskrat are causing severe damage to coastal wetlands. Large alligators feed extensively on coypu, and provide a vital ecological service by reducing coypu numbers.

By Ashleigh Louise. CC BY-ND 2.0, via Flickr

By MajJar. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

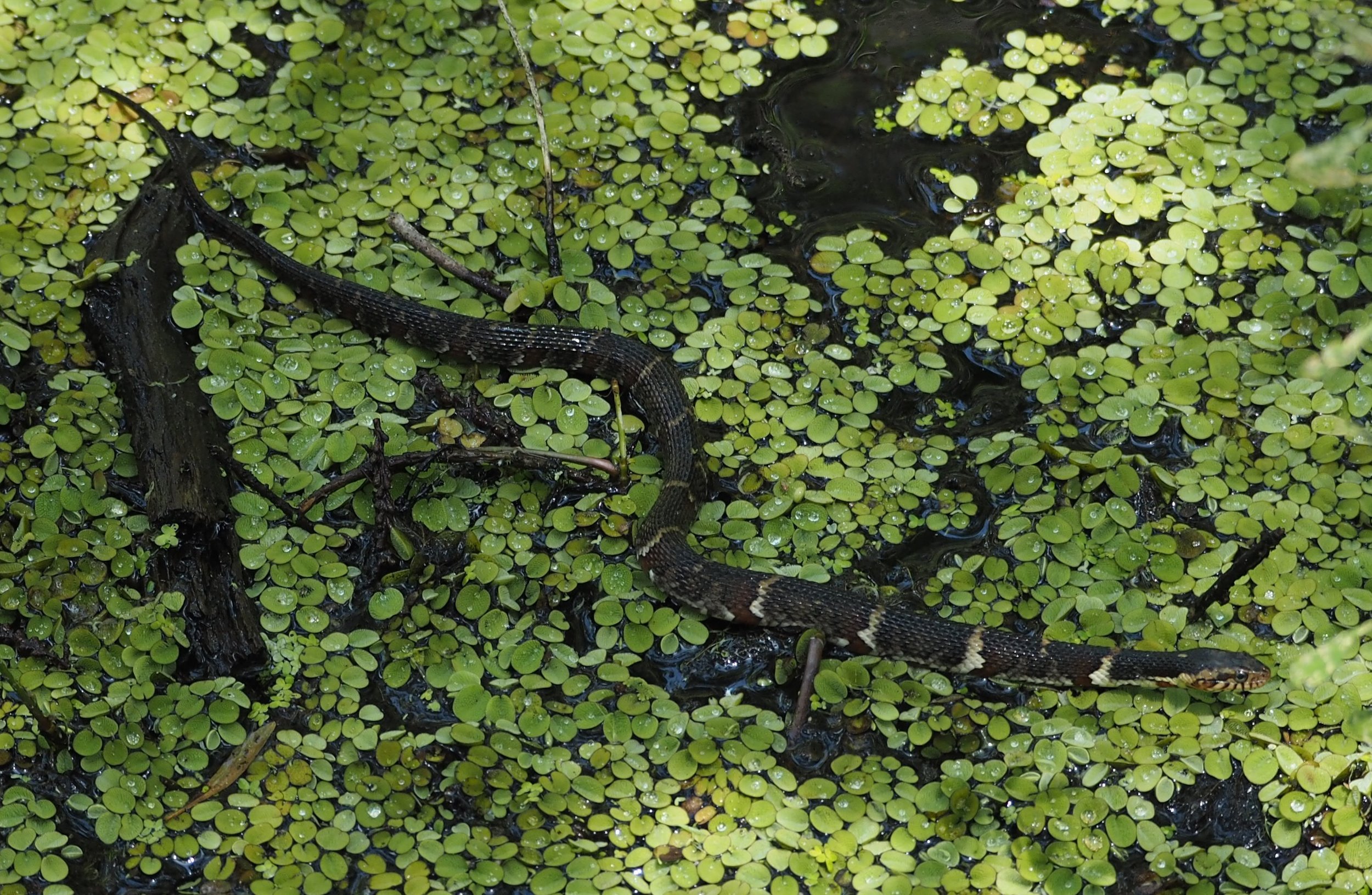

Banded Water Snake

The banded water snake or southern water snake (Nerodia fasciata) is a species of mostly aquatic, nonvenomous, colubrid snake endemic to the central and southeastern United States. It is found from Indiana, south to Louisiana and east to Florida.

Adults of the banded water snake measures from 24" to 42" in total length, with a record size (in the Florida subspecies) of 62.5" in total length. In one study of the species, the average body mass of adult snakes was 16.38 oz.

It is typically gray, greenish-gray, or brown in color, with dark cross-banding. Many specimens are so dark in color that their patterning is barely discernible. They have flat heads, and are fairly heavy-bodied. If irritated, they release a foul-smelling musk to deter predators. Their appearance leads them to be frequently mistaken for other snakes with which they share a habitat, including the less common, venomous cottonmouth.

Nerodia fasciata inhabits most freshwater environments such as lakes, marshes, ponds, and streams. It preys mainly on fish and frogs. Using its vomeronasal organ, also called Jacobson's organ, the snake can detect parvalbumins in the cutaneous mucus of its prey.

The species is ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young. The brood size varies from 9 to 50.

By J. Maughn. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

By J. Maughn. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

Blotched Water Snake

Nerodia erythrogaster, commonly known as the plain-bellied water snake or plainbelly water snake, is a familiar species of mostly aquatic, nonvenomous, colubrid snake endemic to the United States.

This species ranges through much of the southeastern United States, from Michigan to Delaware in the north, and Texas to northern Florida in the south, but it is absent from the Florida peninsula and the higher elevations of the Appalachian Mountains. They are almost always found near a permanent water source, a lake, stream, pond, or other slow moving body. Adults are 24–40 inches (76–122 cm) in total length, and can reach up to 55 inches in some states such as Kansas.

It gets its common name because it has no patterning on its underside. Subspecies can vary in color from brown, to gray, to olive green, with dark-colored blotching down the back, and an underside that is yellow, brown, red, or green.

It is quick to vigorously defend itself by striking repeatedly and flattening its head making it look like a cottonmouth. Which is why it's commonly mistaken for a venomous snake.

This species bears live young (ovoviviparous) like other North American water snakes and garter snakes. In North Carolina and Georgia, the plain-bellied water snake breeds from April to June, and broods of 5-27 young are born in August to October. In 2014 a captive female produced two healthy offspring via parthenogenesis.

By Dawn Casey. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr

Common Snapping Turtle

The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) is a large freshwater turtle of the family Chelydridae. Its natural range extends from southeastern Canada, southwest to the edge of the Rocky Mountains, as far east as Nova Scotia and Florida. This species and the larger alligator snapping turtles are the only Macrochelys species in this family found in North America (though the common snapping turtle, as its name implies, is much more widespread).

The common snapping turtle is noted for its combative disposition when out of the water with its powerful beak-like jaws, and highly mobile head and neck (hence the specific name serpentina, meaning "snake-like"). In water, they are likely to flee and hide themselves underwater in sediment. Snapping turtles have a life-history strategy characterized by high and variable mortality of embryos and hatchlings, delayed sexual maturity, extended adult longevity, and iteroparity (repeated reproductive events) with low reproductive success per reproductive event. Females, and presumably also males, in more northern populations mature later (at 15–20 years) and at a larger size than in more southern populations (about 12 years). Lifespan in the wild is poorly known, but long-term mark-recapture data from Algonquin Park in Ontario, Canada, suggest a maximum age over 100 years.

C. serpentina has a rugged, muscular build with a ridged carapace (upper shell), although ridges tend to be more pronounced in younger individuals. The carapace length in adulthood may be nearly 20 in, though 9.8–18.5", is more common. C. serpentina usually weighs 9.9–35.3 lb. Per one study, breeding common snapping turtles were found to average 11.2" in carapace length, 8.9" in plastron length and weigh about 13 lb. Males are larger than females, with almost all animals weighing in excess of 22 lb being male and quite old, as the species continues to grow throughout life. Any specimen above the aforementioned weights is exceptional, but the heaviest wild specimen caught reportedly weighed 75 lb. Snapping turtles kept in captivity can be quite overweight due to overfeeding and have weighed as much as 86 lb. In the northern part of its range, the common snapping turtle is often the heaviest native freshwater turtle.

By John Brandauer. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr

By John Clare. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr

Copperhead Snake

Agkistrodon contortrix is a species of venomous snake endemic to Eastern North America, a member of the Crotalinae (pit viper) subfamily. The common name for this species is the copperhead. The behavior of Agkistrodon contortrix may lead to accidental encounters with humans. Five subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.

Adults grow to an average length (including tail) of 20–37 in. Some may exceed 3.3 ft, although that is exceptional for this species. Males are usually larger than females. Good-sized adult males usually do not exceed 29 to 30 in, and females typically do not exceed 24 to 26 in. In one study, males were found to weigh from 3.58 to 12.10 oz, with a mean of roughly 6.96 oz. According to a different study, females have a mean body mass of 4.23 oz. The maximum length reported for this species is 53.0 in for A. c. mokasen.

The body is relatively stout and the head is broad and distinct from the neck. Because the snout slopes down and back, it appears less blunt than that of the cottonmouth, A. piscivorus. Consequently, the top of the head extends further forward than the mouth.

The color pattern consists of a pale tan to pinkish tan ground color that becomes darker towards the foreline, overlaid with a series of 10–18 crossbands. Characteristically, both the ground color and crossband pattern are pale in A. c. contortrix. These crossbands are light tan to pinkish tan to pale brown in the center, but darker towards the edges. They are about 2 scales wide or less at the midline of the back, but expand to a width of 6–10 scales on the sides of the body. They do not extend down to the ventral scales. Often, the crossbands are divided at the midline and alternate on either side of the body, with some individuals even having more half bands than complete ones. A series of dark brown spots is also present on the flanks, next to the belly, and are largest and darkest in the spaces between the crossbands. The belly is the same color as the ground color, but may be a little whitish in part. At the base of the tail there are 1–3 (usually 2) brown crossbands followed by a gray area. In juveniles, the pattern on the tail is more distinct: 7–9 crossbands are visible, while the tip is yellow. On the head, the crown is usually unmarked, except for a pair of small dark spots, one near the midline of each parietal scale. A faint postocular stripe is also present; diffuse above and bordered below by a narrow brown edge.

It is found in the United States in the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Northern Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Ohio, Oklahoma, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, East Texas, Virginia and West Virginia. In Mexico, it occurs in Chihuahua and Coahuila. The type locality is "Carolina". Schmidt (1953) proposed the type locality be restricted to "Charleston, South Carolina".[2]

Unlike some other species of North American pit vipers, such as timber rattlesnake and Sistrurus catenatus, Agkistrodon contortrix has mostly not reestablished itself north of the terminal moraine after the last glacial period (the Wisconsin glaciation), though it is found in southeastern New York State and southern New England, north of the Wisconsin glaciation terminal moraine on Long Island.

Within its range it occupies a variety of different habitats. In most of North America it favors deciduous forest and mixed woodlands. It is often associated with rock outcroppings and ledges, but is also found in low-lying swampy regions. During the winter it hibernates in dens, in limestone crevices, often together with timber rattlesnakes and black rat snakes. In the states around the Gulf of Mexico, however, this species is also found in coniferous forest. In the Chihuahuan Desert of west Texas and northern Mexico, it occurs in riparian habitats, usually near permanent or semipermanent water and sometimes in dry arroyos (brooks).

By Laura Wolf. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr

By Natalie McNear. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

Coral Snake

Coral snakes are a large group of elapid snakes that can be subdivided into two distinct groups, Old World coral snakes and New World coral snakes. There are 16 species of Old World coral snake in three genera (Calliophis, Hemibungarus, and Sinomicrurus), and over 65 recognized species of New World coral snakes in two genera (Micruroides and Micrurus). Genetic studies have found that the most basallineages are Asian, indicating that the group originated in the Old World.

Coral snakes in North America are most notable for their red, yellow/white, and black colored banding. However, several nonvenomous species have similar (though not identical) coloration, including the scarlet snake, genus Cemophora; some of the kingsnakes, and the milk snakes, genus Lampropeltis, whose banding however does not include any red touching any yellow; also, there is a genus of shovelnose snake, genus Chionactis, whose color banding actually matches that of a genuine coral snake. No genuine coral snakes in North America, however, exhibit red bands of color in contact with bands of black. So while on extremely rare occasions a certain non-venomous snake might be mistaken for a coral snake, the mnemonic holds true in that a red/ yellow/ black banded snake in North America whose red banding is in contact with its black banding is never a venomous coral snake.

Cotton Mouth Snake

Agkistrodon piscivorus is a venomous snake, a species of pit viper, found in the southeastern United States. Adults are large and capable of delivering a painful and potentially fatal bite. When antagonized, they stand their ground by coiling their bodies and displaying their fangs. Although their aggression has been exaggerated, individuals may bite when feeling threatened or being handled. This is the world's only semiaquatic viper, usually found in or near water, particularly in slow-moving and shallow lakes, streams, and marshes. The snake is a strong swimmer and has even been seen swimming in the ocean. However, it is not fully marine, unlike true sea snakes. It has successfully colonized islands off both the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

The generic name is derived from the Greek words ancistro (hooked) and odon (tooth), and the specific name comes from the Latin piscis (fish) and voro (to eat); thus, the scientific name translates into "hooked-tooth fish-eater". Common names include variants on water moccasin, swamp moccasin, black moccasin, cottonmouth, gapper, or simply viper. Many of the common names refer to the threat display, where this species will often stand its ground and gape at an intruder, exposing the white lining of its mouth. Three subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.

This is the largest species of the genus Agkistrodon. Adults commonly exceed 31 in in length; females are typically smaller than males. Total length, per one study of adults, was 26 to 35 in. Average body mass has been found to be 10.32 to 20.44 oz in males and 7.09 to 8.96 oz in females. Occasionally, individuals may exceed 71 in in length, especially in the eastern part of the range.

Although bigger ones have purportedly been seen in the wild, according to Gloyd and Conant (1990), the largest recorded specimen of A. p. piscivorus was 74 in in length, based on a specimen caught in the Dismal Swamp region and given to the Philadelphia Zoological Garden. This snake had apparently been injured during capture, died several days later, and was measured when straight and relaxed. Large specimens can be extremely bulky, with the mass of a specimen of about 71 in in length known to weigh 10 lb.

The broad head is distinct from the neck, and the snout is blunt in profile with the rim of the top of the head extending forwards slightly further than the mouth. Substantial cranial plates are present, although the parietal plates are often fragmented, especially towards the rear. A loreal scale is absent. Six to 9 supralabials and eight to 12 infralabials are seen. At midbody, there are 23–27 rows of dorsal scales. All dorsal scale rows have keels, although those on the lowermost scale rows are weak. In males/females, the ventral scales number 130-145/128-144 and the subcaudals 38-54/36-50. Many of the latter may be divided.

This is the most aquatic species of the genus Agkistrodon, and is usually associated with bodies of water, such as creeks, streams, marshes, swamps, and the shores of ponds and lakes. The U.S. Navy (1991) describes it as inhabiting swamps, shallow lakes, and sluggish streams, but it is usually not found in swift, deep, cool water.

It is also found in brackish-water habitats and is sometimes seen swimming in salt water. It has been much more successful at colonizing Atlantic and Gulf coast barrier islands than the copperhead. However, even on these islands, it tends to favor freshwater marshes. In various locations, the species is well-adapted to less moist environments, such as palmetto thickets, pine-palmetto forest, pine woods in East Texas, pine flatwoods in Florida, eastern deciduous dune forest, dune and beach areas, riparian forest, and prairies.

By DMangus. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

Diamond Backed Water Snake

Nerodia rhombifer, commonly known as the diamondback water snake, is a species of nonvenomous natricine colubrid endemic to the central United States and northern Mexico.

Diamondback water snakes are predominantly brown, dark brown, or dark olive green in color, with a black net-like pattern along the back, with each spot being vaguely diamond-shaped. Dark vertical bars and lighter coloring are often present down the sides of the snake. In typical counter colored fashion, the underside is generally a yellow or lighter brown color often with black blotching. Their dorsal scales are heavily keeled, giving the snake a rough texture. The dorsal scales are arranged in 25 or 27 rows at midbody. There are usually 3 postoculars.

Adult males have multiple papillae (tubercles) on the under surface of the chin, which are not found on any other species of snake in the United States. They grow to an average length of 30-48". The record length is 69". Neonates are often lighter in color, making their patterns more pronounced, and they darken with age.

The diamondback water snake is one of the most common species of snake within its range. It is found predominantly near slow moving bodies of water such as streams, rivers, ponds, or swamps. Its primary diet is fish and amphibians, specifically slow fish, crayfish, amphiumas (eel-like salamanders), frogs and toads. When foraging for food they will hang on branches suspended over the water, dipping their head under the surface of the water, until they encounter a fish or other prey. They are frequently found basking on these branches over water, and when approached, they will quickly drop into the water and swim away. If cornered, they will often hiss, and flatten their head or body to appear larger. They only typically resort to biting if physically harassed or handled. Its bite is known to be quite painful due to its sharp teeth meant to keep hold of slippery fish. Unfortunately, this defensive behavior is frequently misinterpreted as aggression and often leads to their being mistaken for the venomous cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus), with whom they do share habitat in some places. The brown/tan coloration and diamond-shaped pattern also causes these snakes to be mistaken for rattlesnakes, especially when encountered on land by individuals unfamiliar with snakes.

The diamondback water snake is found in the central United States, predominantly along the Mississippi River valley, but its range extends beyond that. It ranges within the states of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Iowa, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, and Alabama. It is also found in northern Mexico, in the states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz.

While not endangered or threatened, their main threat is human ignorance. Diamondback water snakes are often mistaken for cottonmouths or rattlesnakes and are killed out of fear. In actuality, diamondback water snakes (and other species of water snake) are far more common than the venomous snakes in their range, especially in areas that are frequented by humans.

Like other Nerodia species, diamondback water snakes are ovoviviparous. They breed in the spring and give birth in the late summer or early fall. Neonates are around 8–10" in length. Though their range overlaps with several other species of water snake, interbreeding is not known.

By Natalie McNear. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

By Natalie McNear. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

Eastern Hog-nosed Snake

Heterodon platirhinos, commonly known as the eastern hog-nosed snake, spreading adder, or deaf adder, is a harmless colubrid species endemic to North America. No subspecies are currently recognized. Generally found from eastern-central Minnesota, and Wisconsin to southern Ontario, Canada and extreme southern New Hampshire, south to southern Florida and west to eastern Texas and western Kansas.

The average adult measures 28" in total length (body + tail), with females being larger than males. The maximum recorded total length is 46". The most distinguishing feature is the upturned snout, used for digging in sandy soils.

The color pattern is extremely variable. It can be red, green, orange, brown, gray to black, or any combination thereof depending on locality. They can be blotched, checkered, or patternless. The belly tends to be a solid gray, yellow, or cream-colored. In this species the underside of the tail is lighter than the belly.

Although H. platyrhinos is rear-fanged, it is often considered nonvenomous because it is not harmful to humans. Heterodon means "different tooth", which refers to the enlarged teeth at the rear of the upper jaw. These teeth inject a mild amphibian-specific venom into prey, and also are used to "pop" inflated toads like a balloon to enable swallowing. Bitten humans who are allergic to the saliva have been known to experience local swelling, but no human deaths have been documented.

The Eastern hognose snake feeds extensively on amphibians, and has a particular fondness for toads. This snake has resistance to the toxins toads secrete. This immunity is thought to come from enlarged adrenal glands which secrete large amounts of hormones to counteract the toads' powerful skin poisons. At the rear of each upper jaw, they have greatly enlarged teeth, which are neither hollow nor grooved, with which they puncture and deflate toads to be able to swallow them whole. They will also consume other amphibians, like frogs and salamanders.

They mate in April and May. The females, which lay 8 - 40 eggs (average about 25) in June or early July, do not take care of the eggs or young. The eggs, which measure about 1 1⁄4" × 1", hatch after about 60 days, from late July to September. The hatchlings are 6.5"–8.3" long.

By Kevin Faccenda. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr

By Virginia State Parks. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr

Red-Eared Slider Turtle

The red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), also known as the red-eared terrapin, is a semiaquatic turtle belonging to the family Emydidae. It is a subspecies of the pond slider. It is the most popular pet turtle in the United States and is also popular as a pet in the rest of the world. It has, therefore, become the most commonly traded turtle in the world. It is native to the southern United States and northern Mexico, but has become established in other places because of pet releases, and has become an invasive species in many areas, where it outcompetes native species. The red-eared slider is included in the list of the world's 100 most invasive species published by the IUCN.

Red-eared sliders get their name from the small red stripe around their ears.. The "slider" in their name comes from their ability to slide off rocks and logs and into the water quickly. This species was previously known as Troost's turtle in honor of an American herpetologist; Trachemys scripta troostii is now the scientific name for another subspecies, the Cumberland slider. The red-eared slider belongs to the order Testudines, which contains about 250 turtle species. It is a subspecies of Trachemys scripta. They were previously classified under the name Chrysemys scripta elegans.

The species Trachemys scripta contains three subspecies: T. s. elegans (red-eared slider), T. s. scripta (yellow-bellied slider), and T. s. troostii (Cumberland slider).

The carapace of this species can reach more than 16 in in length, but the average length ranges from 6 to 8 in. The females of the species are usually larger than the males. They typically live between 20 and 30 years, although some individuals have lived for more than 40 years. Their life expectancy is shorter when they are kept in captivity. The quality of their living environment has a strong influence on their lifespans and well being.

These turtles are poikilotherms, meaning they are unable to regulate their body temperatures independently; they are completely dependent on the temperature of their environment. For this reason, they need to sunbathe frequently to warm themselves and maintain their body temperatures.

The red-eared slider originated from the area around the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, in warm climates in the southeastern United States. Their native areas range from the southeast of Colorado to Virginia and Florida. In nature, they inhabit areas with a source of still, warm water, such as ponds, lakes, swamps, creeks, streams, or slow-flowing rivers. They live in areas of calm water where they are able to leave the water easily by climbing onto rocks or tree trunks so they can warm up in the sun. Individuals are often found sunbathing in a group or even on top of each other. They also require abundant aquatic plants, as these are the adults' main food, although they are omnivores. Turtles in the wild always remain close to water unless they are searching for a new habitat or when females leave the water to lay their eggs.

By J. N. Stuart. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr

By Jim, the Photographer. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr

Rough Earth Snake

Haldea striatula (formerly Virginia striatula), commonly called the rough earth snake, is a species of nonvenomous natricine colubrid snake native to the southeastern United States.

The species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1766, as Coluber striatulus. Over the next two and a half centuries its scientific name has been changed several times (see synonyms). Most recently, the generic name was changed back from Virginia to Haldea in 2013. Other common names for Haldea striatula include: brown ground snake, brown snake, ground snake, little brown snake, little striped snake, small brown viper, small-eyed brown snake, southern ground snake, striated viper, and worm snake.

The rough earth snake is found from southern Virginia to northern Florida, west along the Gulf Coast to southern Texas, and north into south-central Missouri and southeastern Kansas.

H. striatula is a small, harmless, secretive, fairly slender snake, 7-10 inches in total length (including tail). It has a round pupil, weakly keeled dorsal scales, and usually a divided anal plate. Dorsally, it is brown, gray, or reddish, and essentially has no pattern. Females are a little longer and heavier than males, with relatively shorter tails. Young individuals often have a light band on the neck, which is normally lost as they mature. The belly is tan to whitish and is not sharply defined in color from the back, unlike in the wormsnake (Carphophis amoenus) or the red-bellied snake (Storeria occipitomaculata). Keeled scales differentiate the rough earth snake from the similar smooth earth snake (Virginia valeriae), as well as from the wormsnake. H. striatula is most likely to be confused with De Kay's brown snake (Storeria dekayi), which is a little larger and is light brown with dark markings on the back and neck. Unlike the rough earth snake, De Kay's brown snake retains these markings into adulthood. Also, S. dekayi has a rounder snout than H. striatula.

The rough earth snake is fossorial, hiding beneath logs, rocks, or ornamental stones, in leaf litter, or in compost piles and gardens. The species is found in a variety of forested habitats with plenty of ground cover, as well as in many urban areas. It can reach very high densities in urban gardens, parks, and vacant lots.

By going on going on. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

By memily. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

Softshell Turtle

The Trionychidae are a taxonomic family of a number of turtle genera commonly known as softshells. They are also sometimes called pancake turtles (although they are distinct from the pancake tortoise). Softshells include some of the world's largest freshwater turtles, though many can adapt to living in highly brackish areas. Members of this family occur in Africa, Asia, and North America. Most species have traditionally been included in the genus Trionyx, but the vast majority have since been moved to other genera. Among these are the North American Apalone softshells that were placed in Trionyx until 1987.

They are called "softshell" because their carapaces lack horny scutes (scales), though the spiny softshell, Apalone spinifera, does have some scale-like projections, hence its name. The carapace is leathery and pliable, particularly at the sides. The central part of the carapace has a layer of solid bone beneath it, as in other turtles, but this is absent at the outer edges. Some species also have dermal bones in the plastron, but these are not attached to the bones of the shell. The light and flexible shell of these turtles allows them to move more easily in open water, or in muddy lake bottoms. Having a soft shell also allows them to move much faster on land than most turtles. Their feet are webbed and are three-clawed, hence the family name "Trionychidae," which means "three-clawed." The carapace color of each type of softshell turtle tends to match the sand and/or mud color of its geographical region, assisting in their "lie and wait" feeding methodology.

Females can grow up to several feet in carapace diameter, while males stay much smaller; this is their main form of sexual dimorphism. Pelochelys cantorii, found in southeastern Asia, is the largest softshell turtle on earth.

These turtles have many characteristics pertaining to their aquatic lifestyle. Many must be submerged in order to swallow their food. Most are strict carnivores, with diets consisting mainly of fish, aquatic crustaceans, snails, amphibians, and sometimes birds and small mammals. They have elongated, soft, snorkel-like nostrils. Their necks are disproportionately long in comparison to their body sizes, enabling them to breathe surface air while their bodies remain submerged in the substrate (mud or sand) a foot or more below the surface.

Softshells are able to "breathe" underwater with rhythmic movements of their mouth cavity that contains numerous processes that are copiously supplied with blood, acting similarly as gill filaments in fish. This enables them to stay underwater for prolonged periods. Moreover, the Chinese softshell turtle has been shown to excrete urea while "breathing" underwater; this is an efficient solution when the animal does not have access to fresh water, e.g., in brackish-water environments.

By Lexi Menth. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr

By vladeb. CC BY-ND 2.0, via Flickr

Western Pond Turtle

The western pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata or Emys marmorata), or Pacific pond turtle is a small to medium-sized turtle growing to approximately 8" in carapace length. It is limited to the west coast of the United States of America and Mexico, ranging from western Washington state to northern Baja California. In May 2002, the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed the Pacific pond turtle as being extirpated in Canada.

The dorsal color is usually dark brown or dull olive, with or without darker reticulations or streaking. The plastron is yellowish, sometimes with dark blotches in the centers of the scutes. The shell is 4.5–8.5" in length. The dorsal shell (carapace) is low and broad, usually widest behind the middle, and in adults is smooth, lacking a keel or serrations. Adult Western Pond Turtles are sexually dimorphic; that is, males have a light or pale yellow throat.

Western pond turtles occur in both permanent and intermittent waters, including marshes, streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. They favor habitats with large numbers of emergent logs or boulders, where they aggregate to bask. They also bask on top of aquatic vegetation or position. Consequently, this species is often overlooked in the wild. However, it is possible to observe resident turtles by moving slowly and hiding behind shrubs and trees.

In addition to their aquatic habitat, terrestrial habitat is also extremely important for Western pond turtles. Since many intermittent ponds can dry up during summer and fall months along the west coast, especially during times of drought, pond turtles can spend upwards of 200 days out of water. Many turtles overwinter outside of the water, during which time they often create their nest for the year.

Western pond turtles are omnivorous and most of their animal diet includes insects, crayfish and other aquatic invertebrates. Fish, tadpoles, and frogs are eaten occasionally, and carrion is eaten when available. Plant foods include filamentous algae, lily pads, tule and cattail roots.

Because of their hard shell, Western pond turtles are generally well protected. However, several predators do threaten this species, especially hatchlings, due to their small size and soft shell.

Raccoons, otters, ospreys and coyotes are the biggest natural threat to these turtles, and hatchlings have the additional threats of weasels, bullfrogs, and large fish.

Finally, this species has the threat of humankind. Due to habitat destruction, this species is currently listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. With the removal of ponds, wetlands, and contamination of other water sources, this species is vulnerable and at risk of becoming extinct without the continuing efforts of reintroducing these turtles to their native range.

By J. Maughn. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr

By Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife. CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr